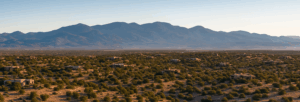

Santa Fe, New Mexico, is a city where architecture is not just a backdrop but a living narrative of its rich cultural tapestry. The built environment reflects a confluence of Indigenous, Spanish, and Anglo-American influences, each contributing to the distinct styles that define the region. This post explores the architectural history of Santa Fe, focusing on key design principles—massing, proportion, emphasis, rhythm, and directional orientation—and how contemporary architects are building on these traditions.

Core Design Principles

Santa Fe’s architecture is driven by a deep respect for the land and the human scale.

- Massing: Homes often maintain a low-slung, horizontal presence, anchoring them visually to the landscape and preserving skyline views.

- Proportion: Buildings prioritize balance and comfort, often using small-scale forms that invite rather than impose.

- Emphasis: Architectural focus points like portals (covered porches), chimneys, or entryways often act as both visual anchors and functional features.

- Rhythm: Repetition of structural elements—vigas, windows, columns—creates a sense of flow that’s both visual and tactile.

- Directional Orientation: Homes typically maximize solar exposure for warmth and light in winter, while shaded portals provide relief in summer, with floorplans oriented around prevailing breezes and views.

Pueblo Style

This is the oldest architectural tradition in Santa Fe, rooted in the Indigenous Pueblo peoples’ building techniques. Key features include:

- Thick adobe walls made of earth and straw, offering thermal mass for natural insulation.

- Rounded corners and soft, organic forms that mimic natural erosion and the contours of the landscape.

- Flat roofs with parapets and canales (roof spouts), characteristic of arid-climate design.

- Prominent vigas and latillas in ceilings, providing both structural and aesthetic rhythm.

Pueblo architecture isn’t just stylistic—it’s a response to climate, culture, and material availability.

Territorial Style

Introduced during the mid-1800s when New Mexico became a U.S. territory, this style overlays Pueblo massing with Anglo-American symmetry and finish details:

- Brick coping atop adobe walls for weather protection and ornament.

- Straight-edged corners and wooden trim around windows and doors.

- Tall, narrow windows and often pitched metal roofs.

- Painted wood columns and portales as nods to Greek Revival and East Coast colonial forms.

This style brought formality and refinement to traditional building methods while maintaining regional practicality.

Northern New Mexico Style

Blending Pueblo and Territorial traits, this hybrid style emerged as a functional response to high-altitude climate and rural simplicity:

- Steeply pitched metal roofs to shed snow and rain.

- Exposed structural elements and porches that serve both functional and social purposes.

- Use of local stone, timber, and stucco, emphasizing durability and low maintenance.

- Homes are often additive, with wings and porches evolving over time.

Contemporary Homage to Tradition

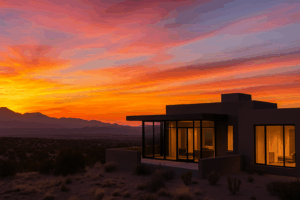

Many of today’s architects in Santa Fe incorporate historical principles into modern work, not as mimicry, but as respectful reinterpretation. The result: clean, minimalist structures that still feel rooted in the land and culture.

- Seth Anderson Studio crafts contemporary homes that embrace Puebloan simplicity while using modern materials like steel, board-formed concrete, and expansive glass. His designs respect traditional massing but often explore contrast through negative space and open-plan interiors.

- Palo Santo Designs integrates passive solar strategies and sustainable building materials, often using adobe and rammed earth in contemporary forms. Their homes reflect the rhythm of traditional Santa Fe buildings while providing open, light-filled living spaces suited for 21st-century life.

- Plan A Architecture focuses on energy-efficient, site-sensitive homes with restrained ornamentation. Their use of traditional elements—such as portals, native stone, or territorial windows—feels intentional rather than nostalgic, offering a calm dialogue between modern design and historical context.

These architects, among others, show that it’s possible to evolve a regional style without erasing its past. Their work proves that modern design can still be timeless, place-based, and inherently Santa Fe.

Conclusion

Santa Fe’s architectural language is one of continuity and adaptation. From the earthy forms of Pueblo villages to the cleaner lines of contemporary homes, the city’s architecture consistently reflects a reverence for proportion, rhythm, and material integrity. As new generations of architects reinterpret these ideas, Santa Fe remains not just a showcase of the past, but a laboratory for future design grounded in centuries of wisdom.